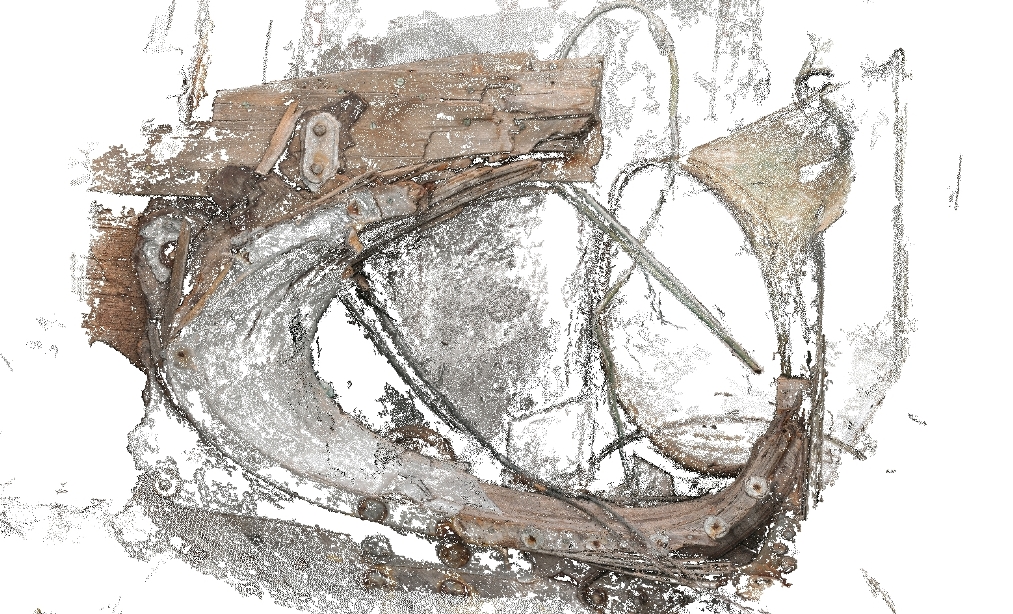

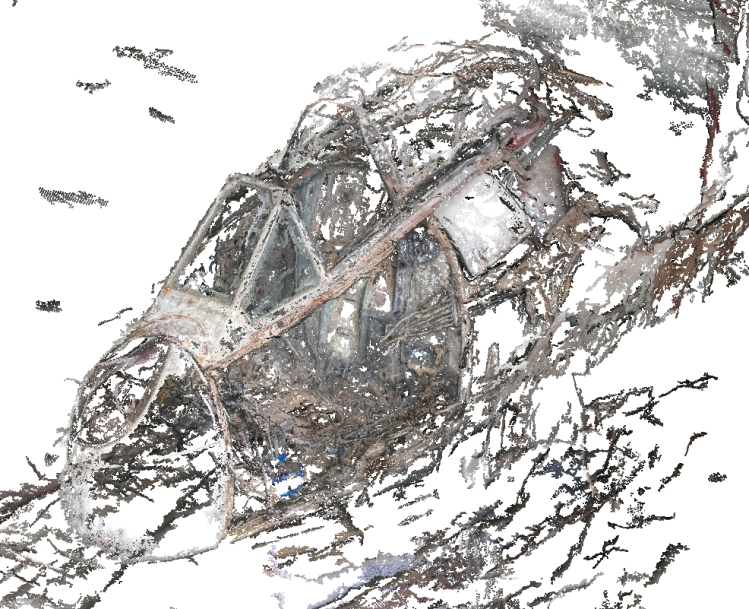

The second panel came to me with three instruments fitted – the A/H (installed upside down!), rate-of-climb and suction-driven T&S.

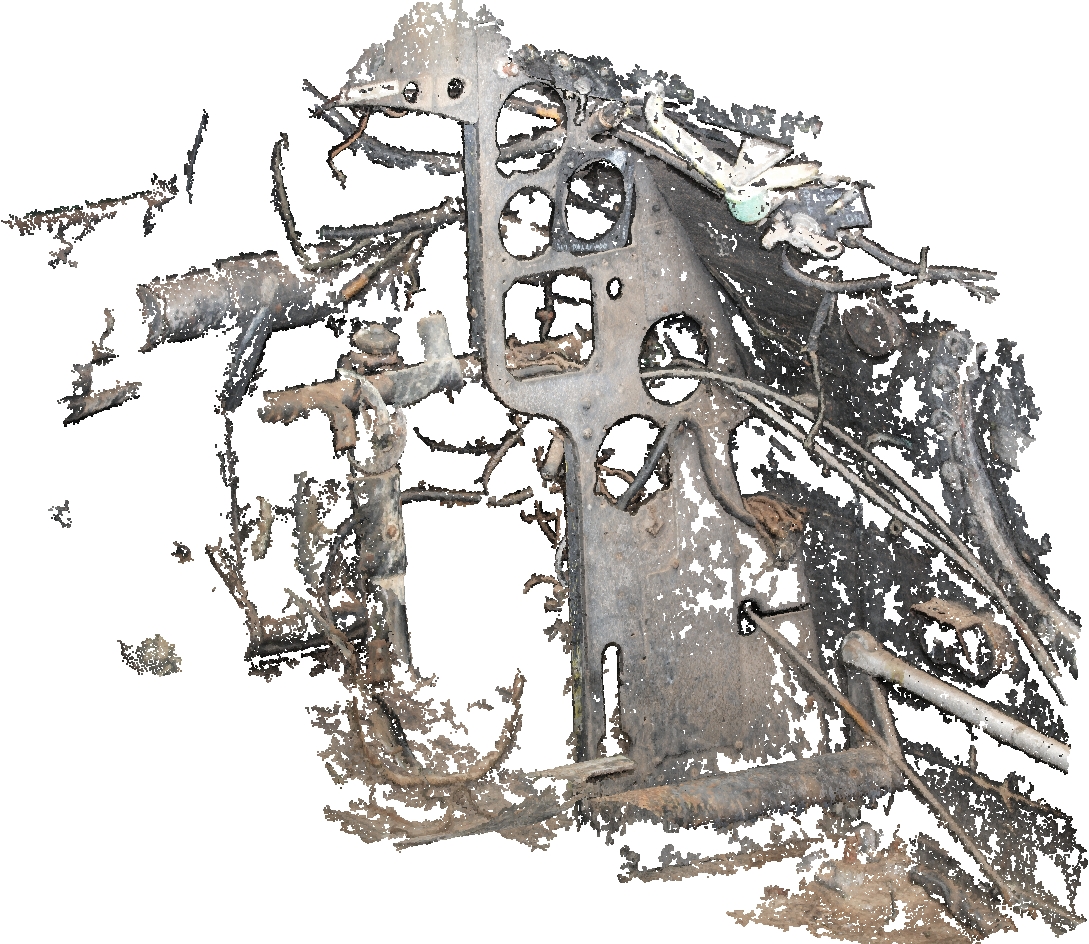

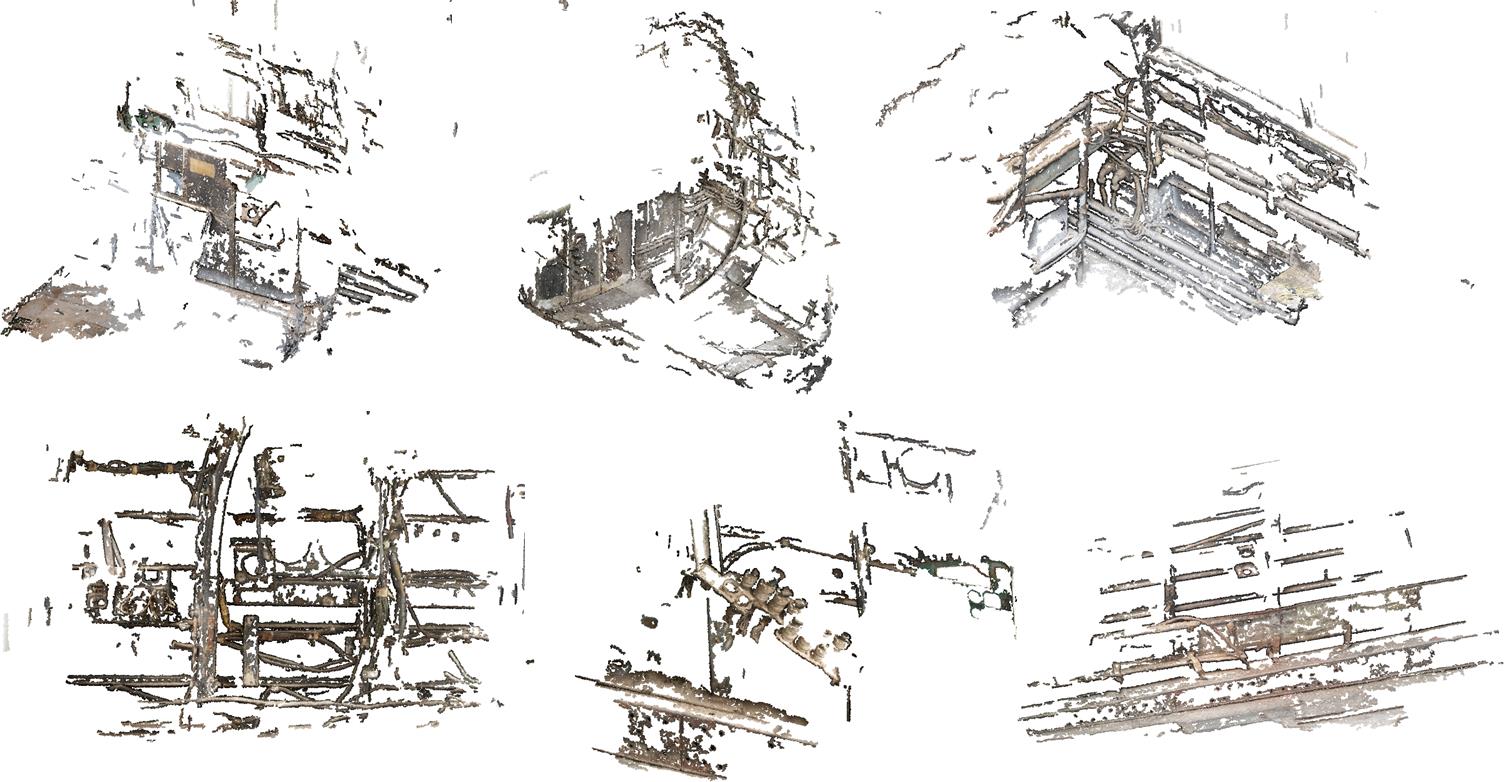

The three mods mentioned in the previous post that replace suction-driven instruments with electric units could be installed progressively. The G3 Compass system could be installed on its own, and was the first of the three modifications issued. The panel restored for A79-175 is actually indicative of this as the suction box attached to the back of the panel still has the open port for the artificial horizon.

The G3F Gyro Magnetic Compass system replaced the Magnesyn Remote Indicating Compass and Direction Indicator gyro; the new system being more accurate than the old. The suction-driven Direction Indicator is simply a gyro that needs to be set to something more accurate, and the performance of suction instruments degrade with altitude.

The artificial horizon mod – introducing the Mk.3 or HL5 – came second and required the G3 compass installation to either have already been installed or to be installed concurrently. With the change for the turn and slip coming later, deletion of the suction-driven A/H required, effectively, a low load for the vacuum system on start, and the union was modified with a pin-holed blank and gauze.

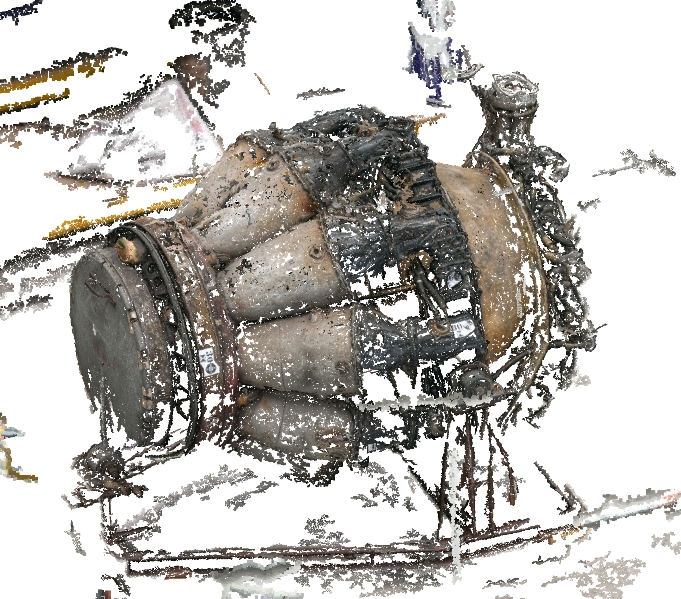

The electric T&S was introduced later, and this was when the entire vacuum system was deleted, including the Pesco pump mounted on the Rotol gearbox, and the suction gauge in the right-hand instrument panel.

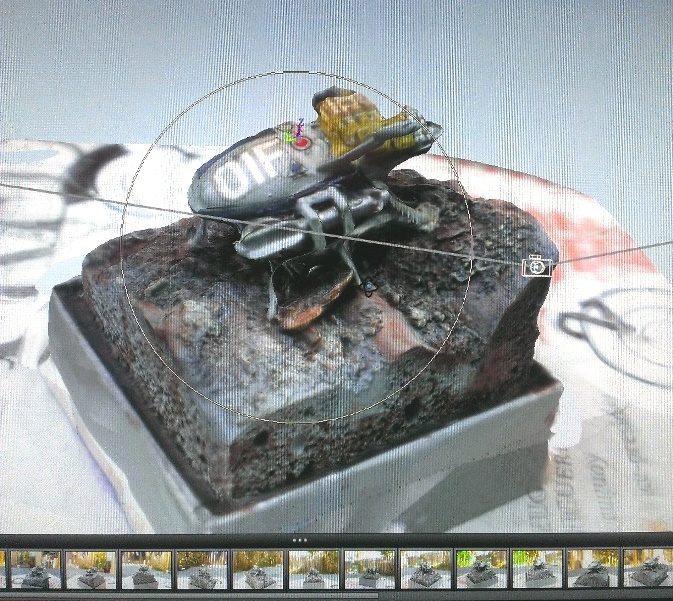

Although A79-733 was modified for the electric T&S, I have restored this BFP with the suction-driven unit that it came with. I have a Hughes Mk.12 electric unit (marked ‘A79-472’, an aircraft that was scrapped at Tocumwal) which requires treatment of corroding magnesium alloy, which I will fit later to reflect the ‘all-electric’ status of ‘733.

Appendix A deficiency list from 8th October 1952 (NAA, Series MP287/1/0, Item 5077/26D) refers to the G6A/500032 ASI. For this panel I have installed what I have; the G6A/500148 has the same Smiths part-number. The obvious difference between the two parts is that the ’032 has a metallic case but the ‘148 has Bakelite.

This panel has the hole pattern for the ASI at around 45 deg. to the usual. The solid rivets used to fill the original holes are obvious. I am not certain that I have chosen the correct orientation for the indicator, but it does match the arrangement in A79-474 which I photographed in the late 1990s.

Air Speed Indicator G6A/500148, Smiths p/n 156AS

Artificial Horizon Mk.3 G6A/2717

Rate of Climb AC-C2 p/n 1636-6A-B1

Altimeter C-12 G106A/500?? (poor condition behind a pretty face!)

Gyro Compass Indicator G3 G6B/500129, Kelvin & Hughes p/n V951

Turn & Slip G6A/3201, CAC Model No. J153 (made by Chivers)